instruction level parallelism

Instruction-Level Parallelism: Concepts and Challenges:

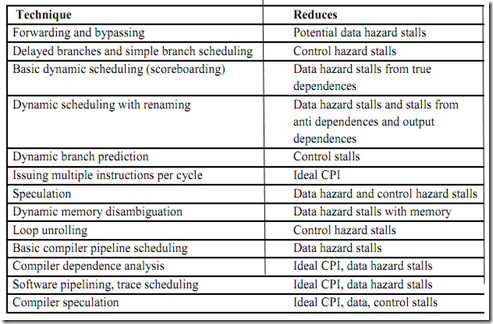

Instruction-level parallelism (ILP) is the potential overlap the execution of instructions using pipeline concept to improve performance of the system. The various techniques that are used to increase amount of parallelism are reduces the impact of data and control hazards and increases processor ability to exploit parallelism

There are two approaches to exploiting ILP.

1. Static Technique – Software Dependent

2. Dynamic Technique – Hardware Dependent

The simplest and most common way to increase the amount of parallelism is loop-level parallelism. Here is a simple example of a loop, which adds two 1000 -element arrays, that is completely parallel:

The simplest and most common way to increase the amount of parallelism is loop-level parallelism. Here is a simple example of a loop, which adds two 1000 -element arrays, that is completely parallel:

for (i=1;i<=1000; i=i+1) x[i] = x[i] + y[i];

CPI (Cycles per Instruction) for a pipelined processor is the sum of the base CPI and all contributions from stalls:

Pipeline CPI = Ideal pipeline CPI + Structural stalls + Data hazard stalls + Control stalls

The ideal pipeline CPI is a measure of the maximum performance attainable by the implementation. By reducing each of the terms of the right-hand side, we minimize the overall pipeline CPI and thus increase the IPC (Instructions per Clock).

Various types of Dependences in ILP. Data Dependence and Hazards:

To exploit instruction-level parallelism, determine which instructions can be executed in parallel. If two instructions are parallel, they can execute simultaneously in a pipeline without causing any stalls. If two instructions are dependent they are not parallel and must be executed in order.

There are three different types of dependences: data dependences (also called true data dependences), name dependences, and control dependences.

Data Dependences:

An instruction j is data dependent on instruction i if either of the following holds:

• Instruction i produces a result that may be used by instruction j, or

• Instruction j is data dependent on instruction k, and instruction k is data dependent on instruction i.

The second condition simply states that one instruction is dependent on another if there exists a chain of dependences of the first type between the two instructions. This dependence chain can be as long as the entire program.

For example, consider the following code sequence that increments a vector of values in memory (starting at 0(R1) and with the last element at 8(R2)) by a scalar in register F2:

Loop: L.D F0,0(R1) ; F0=array element ADD.D F4,F0,F2 ; add scalar in F2 S.D F4,0(R1) ;store result DADDUI R1,R1,#-8 ;decrement pointer 8 bytes (/e BNE R1,R2,LOOP ; branch R1!=zero

The dependence implies that there would be a chain of one or more data hazards between the two instructions. Executing the instructions simultaneously will cause a processor with pipeline interlocks to detect a hazard and stall, thereby reducing or eliminating the overlap. Depend ences are a property of programs.

Whether a given dependence results in an actual hazard being detected and whether that hazard actually causes a stall are properties of the pipeline organization. This difference is critical to understanding how instruction-level parallelism can be exploited.

The presence of the dependence indicates the potential for a hazard, but the actual hazard and the length of any stall is a property of the pipeline. The importance of the data dependences is that a dependence

(1) indicates the possibility of a hazard,

(2) Determines the order in which results must be calculated, and

(3) Sets an upper bound on how much parallelism can possibly be exploited.

Name Dependences

The name dependence occurs when two instructions use the same register or memory location, called a name, but there is no flow of data between the instructions associated with that name.

There are two types of name dependences between an instruction i that precedes instruction j in program order:

• An antidependence between instruction i and instruction j occurs when instruction j writes a register or memory location that instruction i reads. The original ordering must be preserved to ensure that i reads the correct value.

• An output dependence occurs when instruction i and instruction j write the same register or memory location. The ordering between the instructions must be preserved to ensure that the value finally written corresponds to instruction j.

Both anti-dependences and output dependences are name dependences, as opposed to true data dependences, since there is no value being transmitted between the instructions. Since a name dependence is not a true dependence, instructions involved in a name dependence can execute simultaneously or be reordered, if the name (register number or memory location) used in the instructions is changed so the instructions do not conflict.

This renaming can be more easily done for register operands, where it is called register renaming. Register renaming can be done either statically by a compiler or dynamically by the hardware. Before describing dependences arising from branches, let’s examine the relationship between dependences and pipeline data hazards.

Control Dependences:

A control dependence determines the ordering of an instruction, i, with respect to a branch instruction so that the instruction i is executed in correct program order. Every instruction, except for those in the first basic block of the program, is control dependent on some set of branches, and, in general, these control dependences must be preserved to preserve program order. One of the simplest examples of a control dependence is the dependence of the statements in the “then” part of an if statement on the branch. For example, in the co de segment:

if p1 { S1;

};

if p2 { S2;

}

S1 is control dependent on p1, and S2is control dependent on p2 but not on p1. In general, there are two constraints imposed by control dependences:

1. An instruction that is control dependent on a branch cannot be moved before the branch so that its execution is no longer controlled by the branch. For example, we cannot take an instruction from the then-portion of an if-statement and move it before the if- statement.

2. An instruction that is not control dependent on a branch cannot be moved after the branch so that its execution is controlled by the branch. For example, we cannot take a statement before the if-statement and move it into the then-portion.

Control dependence is preserved by two properties in a simple pipeline, First, instructions execute in program order. This ordering ensures that an instruction that occurs before a branch is executed before the branch. Second, the detection of control or branch hazards ensures that an instruction that is control dependent on a branch is not executed until the branch direction is known.

Data Hazard and various hazards in ILP. Data Hazards

A hazard is created whenever there is a dependence between instructions, and they are close

enough that the overlap caused by pipelining, or other reordering of instructions, would change the order of access to the operand involved in the dependence.

Because of the dependence, preserve order that the instructions would execute in, if executed sequentially one at a time as determined by the original source program. The goal of both our software and hardware techniques is to exploit parallelism by preserving program order only where it affects the outcome of the program. Detecting and avoiding hazards ensures that necessary program order is preserved.

Data hazards may be classified as one of three types, depending on the order of read and write accesses in the instructions.

Consider two instructions i and j, with i occurring before j in program order. The possible data hazards are RAW (read after write) — j tries to read a source before i writes it, so j incorrectly gets the old value. This hazard is the most common type and corresponds to a true data dependence. Program order must be preserved to ensure that j receives the value from i. In the simple common five-stage static pipeline a load instruction followed by an integer ALU instruction that directly uses the load result will lead to a RAW hazard.

WAW (write after write) — j tries to write an operand before it is written by i. The writes end up being performed in the wrong order, leaving the value written by i rather than the value written by j in the destination. This hazard corresponds to an output dependence. WAW hazards are present only in pipelines that write in more than one pipe stage or allow an instruction to

proceed even when a previous instruction is stalled. The classic five-stage integer pipeline writes a register only in the WB stage and avoids this class of hazards.

WAR (write after read) — j tries to write a destination before it is read by i, so i incorrectly gets the new value. This hazard arises from an antidependence. WAR hazards cannot occur in most static issue pipelines even deeper pipelines or floating point pipelines because all reads are early (in ID) and all writes are late (in WB). A WAR hazard occurs either when there are some instructions that write results early in the instruction pipeline, and other instructions that read a source late in the pipeline or when instructions are reordered.

Dynamic Scheduling

Overcoming Data Hazards with Dynamic Scheduling:

The Dynamic Scheduling is used handle some cases when dependences are unknown at a compile time. In which the hardware rearranges the instruction execution to reduce the stalls while maintaining data flow and exception behavior.

It also allows code that was compiled with one pipeline in mind to run efficiently on a different pipeline. Although a dynamically scheduled processor cannot change the data flow, it tries to avoid stalling when dependences, which could generate hazards, are present.

Dynamic Scheduling:

A major limitation of the simple pipelining techniques is that they all use in -order instruction issue and execution: Instructions are issued in program order and if an instruct ion is stalled in the pipeline, no later instructions can proceed. Thus, if there is a dependence between two closely spaced instructions in the pipeline, this will lead to a hazard and a stall. If there are multiple functional units, these units could lie idle. If instruction j depends on a long-running instruction i, currently in execution in the pipeline, then all instructions after j must be stalled until i is finished and j can execute. For example, consider this code:

DIV.D F0,F2,F4 ADD.D F10,F0,F8 SUB.D F12,F8,F14

Out-of-order execution introduces the possibility of WAR and WAW hazards, which do not exist in the five-stage integer pipeline and its logical extension to an in-order floating-point pipeline.

Out-of-order completion also creates major complications in handling exceptions. Dynamic scheduling with out-of-order completion must preserve exception behavior in the sense thatexactly those exceptions that would arise if the program were executed in strict program orderactually do arise.

Imprecise exceptions can occur because of two possibilities:

1. The pipeline may have already completed instructions that are later in program order than the instruction causing the exception, and

2. The pipeline may have not yet completed some instructions that are earlier in program order than the instruction causing the exception.

To allow out-of-order execution, we essentially split the ID pipe stage of our simple five -stage pipeline into two stages:

1 Issue—Decode instructions, check for structural hazards.

2 Read operands—Wait until no data hazards, then read operands.

In a dynamically scheduled pipeline, all instructions pass through the issue stage in order (in – order issue); however, they can be stalled or bypass each other in the second stage (read operands) and thus enter execution out of order.

Score-boarding is a technique for allowing instructions to execute out-of-order when there are sufficient resources and no data dependences; it is named after the CDC 6600 scoreboard, which developed this capability. We focus on a more sophisticated technique, called Tomasulo’s algorithm, that has several major enhancements over scoreboarding.